When we moved on to Cocker Hill, Stalybridge many years ago people kept telling us “there used to be a church there” or “The old church fell into the river” etc. I did a little research and found that they were correct, but there had not been just one church though, there had been three, all built in a similar style. The first was built in 1776. It was the first recorded church in Stalybridge and it did fall down shortly after it was built. The next church was demolished around a hundred years later because of structural problems and the last church was demolished in the 1960’s as it was no longer used.

I have detailed the history of the three churches below; you might need to get a cup tea though I think this is going to be fairly long post. The history of the churchyard is interesting too, especially the tales of the body snatchers.

Prior to the building of the Cocker Hill Chapel the people had to walk to either Ashton or Mottram to get to church, not too bad in Summer but it must have been a fairly muddy journey in winter. The church officials in Ashton realised that this was a problem and set about looking for a possible site for a church in Stalybridge.

The site of the church was first sold on 5 May 1698 for £1001.2s.0d. The site measured three acres of “Cheshire large measure” and was described in the deed as “a chance close, a parcel of land”. Nothing was made of the land at that time.

On 30th June 1774 Lord Stamford agreed with the church Commissioners to allow the land to be used to be used for a church. Money for the building was raised by public subscription and by various grants and gifts.

The church was consecrated in July 1776 as “Chapel of St. George in Staly Bridge within Ridgehill and Lanes in the parish of Ashtonunderlyne” (Note how Stalybridge was then two words and Ashton Under Lyne was then one.)

The Rev James Wardleworth was appointed as the first vicar in April 1777. The first Baptisms was recorded were held 28 July 1776 and the first burial in the graveyard took place on 16 January 1777.

The next information I can find for the church is a return made by the church to the articles of enquiry of 1778 sent out by the Bishop of Chester. One question asked about the church services. James Wardleworth answered it as follows:- ” My Chapel had ye Misfortune of Tumbling down on Friday 15th May, 1778 and it is uncertain when it will be rebuilt………”

It appears that the church was rebuilt quickly. I can find no record of the date though. The new church looked very similar to the previous one.

Rev James Wardleworth resigned 4 October 1790 and was succeeded Rev John Robinson on 1 April 1791.

Rev Robinson resigned 9 October 1795 and was succeeded by Rev John Kenworthy 25 September 1796.

John Kenworthy was the vicar for 11 years until he died 13th August 1806.He was just 34 when he died. He was buried in the Cocker Hill churchyard with his wife and Children. The burial records for his family made sad reading. He had a son william who died March 1815 aged 8, a daughter Ellen who died in December 1815 aged 15. His wife Elizabeth died in March 1818 and his other daughter Sarah died in aged just 19 in February 1819.

Rev John Cape Atty was licenced on 11th April 1807. Cape Atty lived on Cocker Hill, opposite the church. In the returns submitted to the Bishop he describes his house as a substantial stone building, with stable and cow-house on the premises. Also a garden” Cape Atty remained vicar until he died in 1822. His memorial stone remains in the Cocker Hill churchyard.

Rev Isaac Newton France was appointed in 1822. France was previously a curate in Ashton. He was reported as creating sects and divisions throughout the church. Things did not seem to go any better for him in Stalybridge and it was reported that “The Chapel at Cocker Hill under his incumbency was deserted to a great extent”. In the year prior to Newton France’s appointment there were reported to be 450 people in regular attendance.

In 1835 Newton France asked the church’s patron, the Earl of Stamford, to close the existing Chapel, due to its bad repair, and build a new one on a different site. I think he though a bigger newer church would get him a bigger congregation. The Earl agreed and purchased the land on the Hague Stalybridge. The foundation stone was laid for the new church 1st September 1838. The church was completed and consecrated 24 June 1840. The new church was called the church of St George, same name as the Cocker Hill Chapel as it was the intention that it the new church replaced the old one; however this was not the case.

The new church, known locally as “New” St Georges, had a capacity of 1,500 people, but with Newton France in charge the congregation was small and it never reached anything near its intended target. Parish records show that the congregation fell as low as six or seven on a regular basis.

Back at the Cocker Hill chapel, known locally as “Old” St Georges, the people were opposed to the idea of closing the church. They petitioned the Bishop to keep the church open and offered to pay for a new vicar to be found. The Bishop gave them permission to make the church safe and good. They did this and even bought a new organ. On the 29th September 1843 Old St Georges re opened with new vicar Rev William Hall. The old Church went from strength to strength and the congregation increased back to the 450 it had been in Cape Attys time.

Then in November 1844 Newton France announced that he intended to leave New St Georges and take up possession of Old St Georges on 1 January 1846.

I think that this decision was mainly due to pew rents and endowments. Basically Old St Georges was making more money than New St Georges and Newton France wanted a piece of it. Because of the difficulties with Newton France Hall resigned from Old St Georges in July 1846 and also resigned as a vicar which seems a shame as it sounds like he was a pretty good one.

Things then went from bad to worse. The newspaper reports at the time implied that Newton France was only returning to old St Georges for financial reasons. He applied to the Church wardens for the keys to the church in August 1846 but his request “was resolutely refused no matter what the consequences”. Newton France then threatened legal proceedings and was told by the Church Wardens that should he insist on returning to the chapel, the congregation would leave and take their organ with them! The Church remained closed. The local MP Mr Tollmache became involved and put the matter before Parliament for debate.There followed a turbulent year with the Churchwarden’s supporters and Newton France’s supporters regularly breaking into the church, changing the locks and taking control of the church.

Newspaper reports at the time suggested that at certain periods on a Sunday in 1847 there were upwards of 2000 people collected in and around the chapel to see what was going on. The week after there were reported to be 3000-4000 people watching to see what would happen next.

By 1849 the church was reported to be very dilapidated, most of the lower windows were broken and the doorway was smashed beyond repair. There did not seem to be any resolution in sight. In May 1850 Isaac Newton France died. A coroners inquest gave a verdict of “death by natural causes”.

Following the death of Newton France the Bishop of Manchester appointed a new vicar at old St Georges, Rev John Leeson. Leeson had taken over new St Georges after Newton France and had grown and gained the respect of the congregation there. The Bishop hoped that he would help heal the problems in old St Georges.

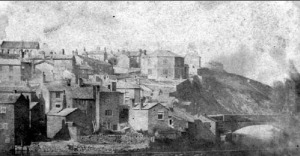

The Second Old St Georges with surrounding buildings. This photo was taken some time after 1848 when Wakefield Road Baptist Church, the Church on the top left of the picture, was built.

Leeson continued to have many problems with the churchwardens at old St Georges so perhaps all the trouble at old St Georges wasn’t Newton France’s fault. Leeson appeared to deal with them better though and won in the end. John Leeson continued at old St Georges until his death in August 1867. His memorial in the Cocker Hill churchyard is still visible and says; “This Monument was erected by many friends and is sacred to the memory of John Edmund Leeson who for 16 years was incumbent of this church……”.

Rev John B Jelly Dudley was appointed vicar in 1867 and continued for 34 years until his death in 1904. He was described as a “flamboyant figure with a great sense of humour”

In February 1877 it was reported that an “alarming landslip occurred at old St Georges churchyard” part of the churchyard had collapsed down the hill and exposed number of coffins. News of the landslip spread rapidly and hundreds of people lined the Stamford Street Bridge to try to see what had happened.

In 1880 and 1881 church records show that “cracks had begun to appear in the south west corner of the building” The cracks got bigger and on 10th July 1882 the church was officially closed for safety reasons.

In 1886 a contract was drawn up to construct a new church on the same site. The new church was octagonal as the previous ones but the roof and windows were different.

The church was re opened in 1888 and was described by the local paper as “an improvement on the old”

In 1904 old St Georges gained a new vicar; Rev Herbert Hampson. He was well liked and introduced both a dramatic society and an athletic society to the church. He continued as vicar until he died in September 1924. Hampson was succeeded by Rev Frank Augustine Whitehead who was vicar from 1924 to 1937. Whitehead was described as “a great encouragement” and was a supporter of the dramatic society and was the only vicar known to perform in the dramatic productions.

The next vicar was Rev Reginald Hugh Cadman who stayed 7 years and appeared to have a fairly uneventful time at the church.

Cadman was succeeded in 1946 by Rev Charles James Saunders. Tragically Saunders committed suicide two years after taking over the church. Saunders had received the Military Cross for service during the First World War and it was thought that he had suffered from Shell shock. His time at the church was a strange one; not long after he arrived many of the parishioners of the church began to receive defamatory and insulting letters. Though none of the accusations in the letters were true they caused upset in the congregation and the police were called. The police noted that all the letters that had been typed were typed on the vicar’s typewriter and the letter that had been handwritten was in the vicar’s handwriting.

The next vicar was Rev William George McGowan was appointed in 1949. He was a “much loved and admired” vicar but decided to move on after just four years. At that point talk began again of closing old St Georges.

Rev John Penrose was appointed in 1954 and he stayed just three years. The building had fallen into disrepair again and cracks had begun to appear in the North wall. Architects’ reports showed that there were serious problems with the building and that is perhaps one of the reasons why John Penrose left the church.

In 1958 Rev William Radcliffe was appointed vicar and he too stayed just three years.

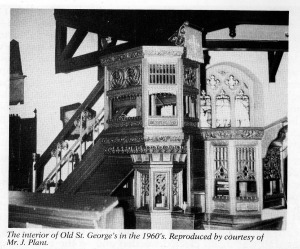

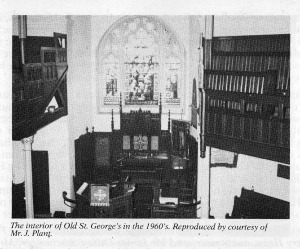

Third Old St Georges Church in the late 1950s/1960s. Note the cross on the wall which was illuminated at night.

Radcliffe was succeeded in 1962 by the last vicar of old St Georges Rev Micheal Hodge. Hodge remained vicar for five years until the church closure in 1967. Records show over 150 attended the final service in September 1967 and 80 attended the farewell dinner.

A great deal of effort was extended to try to preserve the building. In 1967 the Stalybridge Civic Society were interested in turning the building into a theatre. The Bishop agreed and said the building would be given as a gift to the town on condition that it would be maintained in a dignified manner. Unfortunately nothing came of this and the building was demolished.

Prior to demolition the majority stained glass windows were moved into storage; unfortunately they were later destroyed b a fire. The “Ruth and Naomi” window was moved to Mottram Parish Church. A number of the pews went to Holy Trinity, Bardsley, the Church Bell went to the Church of St Stephen, Astley and the font went to new St Georges in Stalybridge. The wooded reredos were sold to the Ealing FilmStudios along with one or two pews. The reredos was used on the set of the film “Cromwell”

The Cocker Hill churchyard remains today and you can still see the outline of old St Georges and the memorials to Rev Leeson and Rev Cape Atty.

New St Georges continues to be a living church. Website http://www.stg.org.uk/

Sources

Two into On will Go by Paul Denby ISBN 0 9515993 0 5

Looking back at Stalybridge ISBN 0904506150

Burial Records Old St Georges

If you want to know more I can definitely recommend the book “Two into one will go” by Paul Denby ISBN 0 9515993 0 5. The book has the full history of both churches together with a full chapter on the battle between Isaac Newton France and the ChurchWardens. There is also an account of the battle between Isaac Newton France and the Churchwardens in the book “Looking back at Stalybridge” Edited by Alice Lock ISBN 0 9515993 0 5.